I am a retired United Church of Canada minister living in Lunenburg, Nova Scotia.

On this webpage, I'm sharing some highlights of my work in which I was engaged from 1978 - 2023. This webpage is a work in progress and I'll be adding bits and pieces as time goes on.

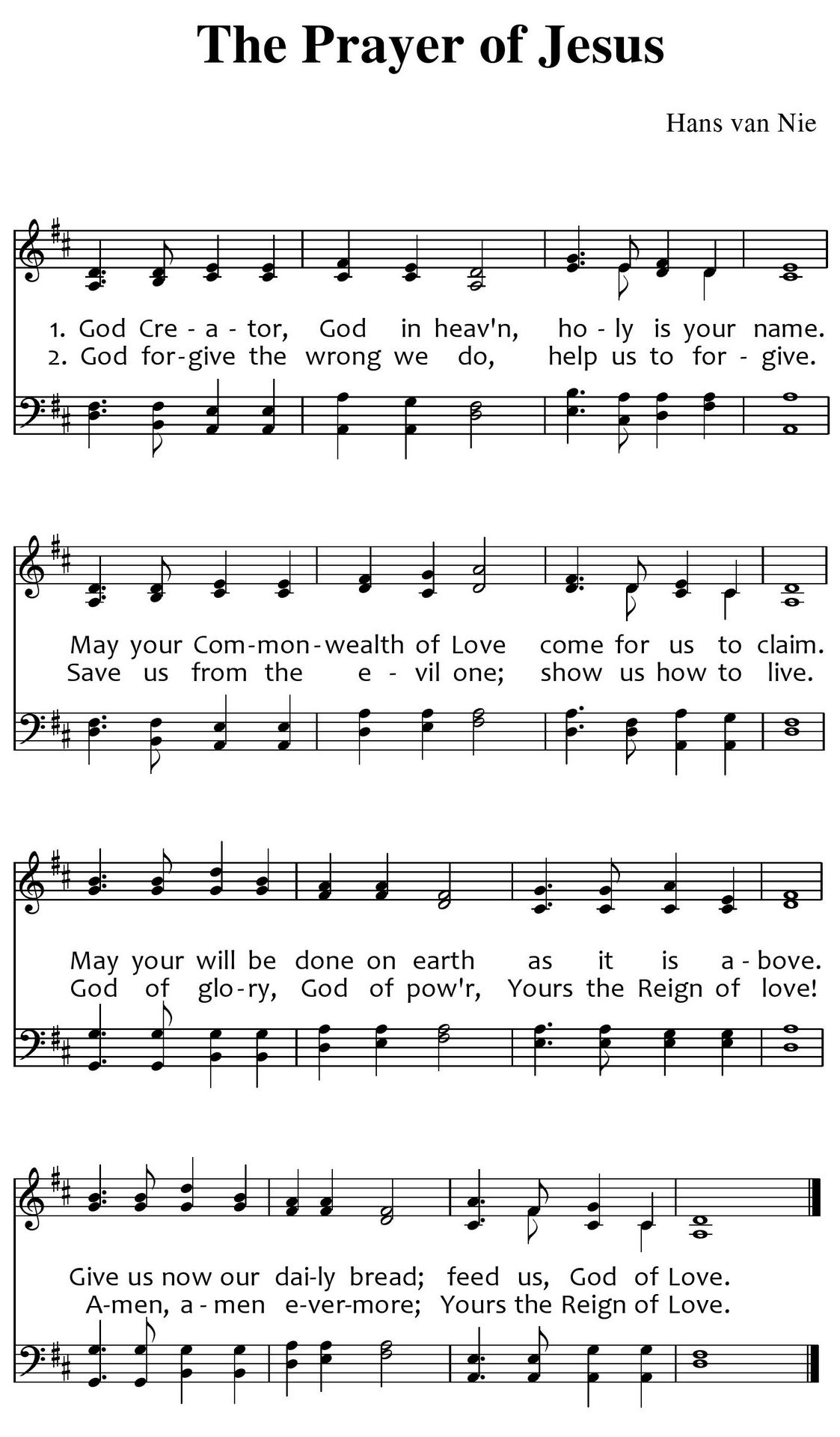

My reflections on the Prayer of Jesus (the "Lord's Prayer") can be found below:

You may also be interested in my work on the United Church's Song of Faith (see menu above)

The Christian faith tradition features a foundational prayer, taken from the teachings of Jesus. This prayer sums up some basic aspects of the Christian faith and is used by all Christians in liturgies for communal worship as well as personal devotions. In an attempt to render this prayer in contemporary language, I have composed a musical version which was well-received in the congregations with which I have worked.

“God, Creator, God in

Heaven”

Scriptures: Deuteronomy 32:1-6;

10-12, Matthew 6:7-13

The familiar version of the Prayer of Jesus begins with the phrase, “Our

Father who art in heaven.” Generally

speaking, the prayer of Jesus is meant to be a paradigm prayer for the gospel

community; it gives us a pattern for prayer.

As such, the prayer of Jesus is not meant to be idolized or to be seen

as some untouchable formula that cannot be paraphrased or interpreted. Such institutionalization would be out of

character with the teaching of Jesus.

Jesus teaches with the constant use of metaphors, symbols and parables

that cry out for elaboration and application.

There is no reason why the prayer of Jesus should not be included as

that sort of teaching. So Jesus begins

the prayer by using a metaphor in addressing the Holy One. The

prayer of Jesus is addressed, of course, to the God of ancient Judaism. This was the God who liberated the people of

Israel from slavery, the God who called those people to live together as

siblings who care for each other in a national family of tribal groups. Sometimes the God of Israel was considered to

be a parent figure for the people. So we

read in the ancient “Song of Moses": “God found Israel in a desert land, in the

howling waste of the wilderness; God encircled and cared for the people,

they were kept as the apple of God’s eye. Like an eagle watching her nest, hovering

over her young, God spread out her wings to hold them, supporting them on

her pinions.” (Deuteronomy 32:10,11) In this beautiful metaphor, God is seen as a mother eagle

caring for her chicks, teaching them to fly, raising them to maturity. Elsewhere in this same song God is named as a

father figure; the song asks, “Is not this your father, who gave you being, who

made you, by whom you subsist?” (Deuteronomy 32:6b) Such scriptures indicate that the people of

Israel were moved at times to picture God as a parent who had given birth to them

and who looked after them.

The culture of Israel and subsequently

Judaism, turned out to be strongly patriarchal, probably less so at the

beginning, but certainly more so by the time we get to the days of Jesus. Therefore the parental role of God became

almost entirely focused on the role of the father, even though the maternal

dimensions of God had also been portrayed earlier in the tradition. Jesus speaks in the patriarchal language of

his time when he begins the prayer by saying, “Our father in heaven.” The point of this statement is not to let us

know the gender of God, but it is to focus attention on God’s role as

parent. As far as that goes, we could

just as well say, “Our mother in heaven.”

In fact in today’s world, where many folk are growing up in families

where fathers are either absent or abusive, it may not be particularly helpful

to call on the metaphor of God as father.

For some people, at least, a mother metaphor would be much more helpful. At any

rate, Jesus sees God as a parent for us and so we are seen as God’s

children. We are all children of human

parents and we know what it means to be children. As children of human parents we are shaped by

the genetic material and family influence of our parents. Sometimes we can identify character traits

and attitudes that have been passed on to us by our parents. The idea of naming God as a parent in heaven

is to affirm that we may also have character traits and attitudes that are

shaped by God our creator in whose image we have been created. We often speak of God as a “person” with

personal characteristics and attitudes.

We acknowledge God’s love and compassion, we talk about God’s sense of

justice and righteousness, we say that God is good and that God cares about

us. This personality of God is as good

as we can imagine any personality to be; in a sense too good for this world and

therefore a heavenly personality. At the

same time, because we are God’s children, we have inherited some of God’s

heavenly personality, or at least the capacity to develop godly characteristics

and attitudes of love and compassion, justice and goodness.

If we

have trouble trying to understand what someone would be like with a character

and personality inherited from our parent in heaven, we need only look at the

person of Jesus to see what that is like.

In fact, as followers of Jesus we claim that Jesus inherited God’s

personality fully and completely. Not

only was Jesus molded in God’s image like all the rest of us, Jesus also

reflected and lived God’s image perfectly.

Nowadays we might say that Jesus was a “clone” of God as far as the

heavenly personality of Jesus is concerned.

As such, Jesus exhibits God’s love and compassion, God’s goodness and

righteousness. It is also interesting to

note that Jesus exhibits the parental concern of the heavenly parent which is

both fatherly and motherly. Jesus takes

on the same parental metaphors that are used for God in the tradition of Israel

such as the good shepherd and the mother hen.

In one passage, Jesus looks at Jerusalem and says, “How many times have

I wanted to put my arms round all your people, just as a hen gathers her chicks

under her wings.” (Matthew 23:37) In the biblical parental metaphors, we see a

strong focus on the use of the images of “wings” and “arms.” A chick is safe under the wings of mother

eagle or hen. A child is safe in the

arms of its parent. Human living has always been precarious. One wrong move can result in injury or

death. We need guidance and protection -

as children and also as adults. As

children look to their parents for guidance and protection; in a broader sense

we look to God for the same. We sense

that when we follow God’s guidance we are on a path which provides a level of

security and safety which otherwise eludes us.

As Christians we find such safety in following Jesus, as we live in the

Way of Christ. Then we are “safe in the

arms of Jesus,” as an old hymn says.

At the

same time, Jesus is both parent and child, identifying with God but also

identifying with us. As our sibling,

Jesus calls us to live the image of God within ourselves as well. We too have inherited a capacity for heavenly

personality. We too can live that

personality and we do so by putting that personality in action in our

relationships with each other. That

means of course that when we don't manage to live together in love with each

other that we exclude ourselves from the family of God. Based on the teaching of Jesus, the New

Testament claims that those who do not love their sisters and brothers are not

God’s children. We can call God our

“father in heaven” all we want, but if we do not live in love with our sibling

children of God, it is all for naught. We

cannot really know the personality of our heavenly parent unless we live that

personality ourselves. When we are

finally able to sense deep love for someone of whom we don’t approve one bit

then we know what is in the heart of God.

When we are finally able to respect the life of someone we had seen as

worthless, then we know the mother-love of God for every human creature. When we are finally able to accept someone

who has hurt us badly, then we understand the profound mercy of a good father

in heaven. When we are finally able to

make some major sacrifices of our wealth, our time, our very being, then we are

living the image of God who freely gives to us all there is to give. So we need

to be living together as sisters and brothers in Christian love before we can

even begin to invoke the name of our mutual mother or father in heaven. Then, when we do begin to love and respect

each other, we also grow into relationship and communion with God. When we start to work along with the Spirit

of God to bring friendship and healing and peace to each other, then we grow

close to our heavenly parent for whom these things are a matter of course. If my

mother were a potter she could explain to me how to make pottery, but unless I

get my hands into the clay and mold it on the wheel and feel the pot taking

shape over and over again until it is just right, I will not know the working

of her mind that enables her to do the pottery, and I would never be able to

make a pot myself. If my father were a

sailor he could tell me stories about the sea but unless I sail with him, feel

the swaying deck beneath my feet, feel the ocean wind in my face, I will never

know the sailor within his person. With

God it is even more important that we engage in godly living together with our

heavenly parent, for we do not see God, we only get to know God’s personality

as we live our lives as God would live if God were here with us. Fortunately we know what God would be like in

the flesh with us for we have seen God in the flesh in Jesus. Put some potters together in a group and

there is an instant rapport of mutual understanding about pottery. The same goes for sailors and sailing. And yes, it should also be so for the

children of a mother or father in heaven.

Therefore the prayer of Jesus says “our father in heaven,” not “my

father” even though Jesus often uses that first person pronoun elsewhere. The heavenly parent belongs to all of us

together and all of us who know what it is to live the love of God have the

right to name our heavenly parent as we begin our prayers.

Just

exactly how we name our parent in heaven will depend on the way we have come to

know the personality of God as we ourselves have lived God’s love. That parental personality cannot be

restricted to any one metaphor. It

cannot be exclusively father or mother or good shepherd or mother hen, it might

be none of these but something else, another metaphor that seems just right in

naming the personality of God. Father,

Mother, Maker, Creator, Life-giver, Lover, all of these and more have been used

as good translations and paraphrases for the One who is addressed in the prayer

of Jesus. Whatever word we use to name

the One in whose image we are created, that metaphor will always affirm the

close relationship in personality that we share with God and with each

other. As followers of Jesus, we know

that personality best in Christ. It is a

personality of great compassion, exquisite goodness and perfect

righteousness. It is the personality of

the one who loves each one of us with unlimited compassion. Whenever

we begin to pray, when we make our connection with the source of our existence

we name our heavenly parent as best we can: God; Creator; our Life-Giver in Heaven; Father and Mother of us all.

“Holy is Your Name” Scriptures: Exodus 3:13-15, Acts 3:1-6

In the

prayer that Jesus taught us, we address God and then we say, “holy is your

name.” There is something special about

the name of God. God’s name is holy. The word holy means “set apart, beyond the

ordinary, very special.” For the Jewish

people, God’s name is so holy that it cannot be spoken out loud. In fact we have more or less forgotten what

it sounds like. In the original Hebrew

Scriptures we have only the consonants of God’s name. That would be as if your name was Elizabeth

and we only had the L, the Z, the B and the TH.

It would be anyone's guess how to pronounce your name once the original

vowel sounds had been forgotten. There

have been, of course, some guesses about the pronunciation of God’s name. A century or so ago some scholars came up

with the pronunciation “Jehovah” but that was almost certainly incorrect and

today’s scholars pretty well agree that the pronunciation should be more like

“Yahweh.”

A name

should tell something about a person. In

many cultures names are given to describe a physical feature or an event that

coincided with a person’s birth. There

is a fellow in the bible called Esau, which means “Red;” he probably had red

hair. We have more or less lost this

custom in our culture and yet we often give people nicknames which describe

their looks or character or place of origin.

When I was a boy as a new immigrant from Holland, I came to be called

“silver skates” from the book about my namesake Hans Brinker. Others had more mundane nicknames like

“shorty” or “speedy” or “rusty.” We

sensed that the nickname fit the person in some way. God’s name fits too of course. “Yahweh” comes from the Hebrew verb “to

be.” Yahweh is the name of the divine

being or force in the universe that simply is.

When God was revealed to Moses in the burning bush Moses asked God, “But

what is your name?” And God said, “I am

who I am. I am called ‘I AM’ - ‘Yahweh.’ ”

When

you know somebody’s name you can have a relationship with that person. When you call a person’s name that person

responds. When you speak a person’s name

you are aware of that person; the whole person comes to your mind. A name is more than a label; it is a symbol

for the whole person. That’s why lovers like to carve their names inside a

heart in a tree, or mark them in the sand.

The joining of their names inside that symbolic heart signifies the

intimate relationship those two persons have together. When puppy-love afflicts a teenager we find

the name of the loved one written all over the school books. When a baby is born, the new parents speak

the name over and over again to the baby.

We speak a person’s name out loud in baptism thereby affirming who that

person is: a unique and precious person; God’s beloved child, created in God’s

image and given a name, a special name of their own so that we will know who

that person is. We speak each other’s

names to affirm our identity and we give names to God in order to acknowledge

God’s identity. Calling on the name of

God brings the person of God into our awareness and helps us know that God is

there with us.

Some

people will say, “That is all fine and dandy, but rather wishful thinking on

the part of a believer.” And I must say,

we human beings do set up for ourselves our false gods with wishful, fancy

names. Think for a moment about the

names that we give to some of our most important idols: Magic Wagon, Saturn,

Solar, Regal, Supreme, Excel, Panasonic. I would rather buy a car or a

television or a wristwatch with one of those magic names. Those magic names conjure up visions of

pleasure and delight that is out of this world.

Interestingly enough, as children of God in heaven we are much more down

to earth in our naming of God. When we

get right down to it, we simply call on God as a being, as Yahweh, the One who

is there with us. Our God does not

perform magic. Our God does not give us

fancy thrills and exciting pleasures.

Our God simply is, and that is enough for us. That has been enough for countless believers

who have called on God’s name, recognizing that God would be with them in good

times and bad. This is not wishful

thinking but a matter of human experience; God has been there. God is there, a real presence of whom we are

aware when we call God’s name.

For

Christians, the most profound expression of God’s presence has come in and

through the person of Jesus. Jesus

embodied that which is of God: love, mercy, grace, wholeness, truth,

compassion, goodness. The presence of

God in Jesus brought life and health and well-being to broken people who came

to know Jesus. Even after Jesus had

gone, the presence lingered on, more powerful than before. In that lingering presence we have come to

equate the presence of God with the person of Jesus. And again, we call that person by name, so

that when we speak the name of Jesus we are calling on the presence of

God. That is why we have trouble with

people who use the name of Jesus flippantly.

That is why we are shocked when someone uses the name of Jesus to

express their anger and frustration.

Surely we mock all that is sacred to us when we invoke the presence of

God in moments of rage, disgust and violence.

It is sad to think that people need to curse and swear in anger and

bitterness when they could instead be calling on that same name of Jesus to

relieve and save them from their misery.

Most tragic of all is the seasoned veteran of profanity who tries to

obliterate all faith in goodness and ignore all hope for wholeness by wallowing

in a life of despair punctuated by repeated outbursts of the name of God and of

Jesus Christ.

We are

not all habitual cursers of course. But

how much respect do we have for the name of Jesus? How does it compare with that of the

disciples in the early Christian community?

It seems that those folk found their entire source of strength and all

of their resources for ministry in the name of Jesus. That’s how the book of Acts presents the

story to us. In Acts chapter 3 we hear

about Peter and John who met a person begging for money at the gate of the

temple. Peter and John were poor

themselves and didn’t have any money to give, so instead Peter said to the

person, “I have no money at all, but I will give you what I have: in the name

of Jesus of Nazareth, walk!” ( Acts 3:6)

Later on in the chapter Peter explains to the astonished onlookers, “It

was the power of the name that gave strength to this person. What you see and know was done by faith in

the name of Jesus.” (Acts 3:16) So the

story tells us that the power of the name of Jesus brought new life to someone

who had not much of a life at all. There

are aspects of this story that are difficult for us. We wonder about the faith-healing that

appears to take place. We have heard too

many stories about phony faith-healers and we have seen too many of our friends

go through illness and death even when their faith was very strong. The details themselves of the story raise

questions: If indeed God had wanted this

person to be healed, why had Jesus not healed the man on one of many visits to

the temple? The story says that the man

had been ill all his life and that he was brought to the temple each day; so

Jesus too must have passed by him many times.

Some interpreters explain the story on the basis of symbolism related to

it. Often in the bible blindness is a

symbol for ignorance and lameness is a symbol for weakness. There is a story about Jacob who struggles

with the presence of God one night and is left lame as a result. Consequently, Jacob’s offspring, the people

of Israel, are often called “the lame ones” who are to be rescued by God and gathered

into a new community. The healing of the

lame man may well be a symbolic story which is a sign to a new Israel that the

new community has come into being. And

so the granting of sight to the blind and strength to the lame means that

people are now able to see God’s new community and to walk in the footsteps of

Jesus with sufficient strength to overcome the obstacles in the way.

No

matter how we interpret the story, it is essential that we see it in the larger

context of the community of faith and the role that the name of Jesus played in

that community. Although our story tells

of healing in the name of Jesus, it is not a short course in

faith-healing. This story is not meant

to say that anyone can be healed of anything at all as long as they have enough

faith and as long as they know the magic combination of words to use as they

invoke the name of Jesus in just the right way. If we think we can find a magic formula for

healing, just the right prayer, then we are really only dabbling in wizardry

and witchcraft and we have strayed far from genuine faith in God. Instead, our story is one segment of a larger

story that describes a community which

finds its identity

and its strength in the name of Jesus.

The community of which Peter and John were a part had no resources

except for one thing - the awareness of God’s presence through calling on the

name of Jesus. They had no money, as our

story says. They had no formal

organization, no church structure as yet.

They had no public authority.

Their profile as a social group was insignificant and had to be kept

very low because they were associated with someone who had been put to death as

a criminal. They were seen as a

disgraceful bunch with nothing at their disposal. They had nothing but the name of Jesus. And it wasn’t just that they experienced

occasional healing in the name of Jesus but they began to live their whole

lives in the name of Jesus. They greeted

each other with signs of peace in the name of Jesus. They had meals together as a community in the

name of Jesus. They baptized in the name

of Jesus. They reached out to the poor

and the sick in the name of Jesus. Even

when they had nothing to give; no food, no money, no medicine, they still

reached out with good-will and friendship and compassion in the name of Jesus

because that’s what Jesus had done as God’s presence with them. So the main point of our story is to present

the “life-style” of the community of the followers of Jesus. The fact that they had no material goods to

give did not stop them from giving what they had to the world around them. And they had much to give: love and mercy,

grace and wholeness, truth and compassion.

When we

call on the name of Jesus we acknowledge the presence of God-with-us which

Jesus represents. When we reach out to

others in the name of Jesus we acknowledge in them the presence of God which

Jesus represents. That is a powerful

acknowledgement, an invocation that can transform us dramatically and reveal

God’s presence and purposes in the world around us. So it is that in our praying, in our living,

in our baptizing, in all of our ministry, we name our God in heaven with a name

that is holy and precious to us; a name we Christians have come to know as the

name of Jesus who is our Christ: the Way, the Truth, and the Life.

“The Commonwealth of Love” Scriptures: Micah 4:1-4, Luke 14:15-24

Every

time we pray the prayer that Jesus taught us, we pray for the coming of God’s

reign: “Thy kingdom come, thy will be

done on earth as it is in heaven.” All

of that belongs together. The doing of

God’s will on earth means that God’s reign is happening. Wherever God’s purposes are being

accomplished, God’s reign has begun.

Wherever human beings are living the gospel, the kingdom is

arriving. Perhaps the word “kingdom” is

not the best word to describe the reign of God.

In the gospel community, the royal authority of God is distributed

through the gifts of the Spirit among the citizens of the community. The One who reigns does so at a “grass-roots”

level. From the point of view of gospel

citizens such a community is as much a commonwealth as it is a kingdom. It is a common-wealth where the resources

provided by God are shared in peace and harmony with a generous love. It is very much a “Commonwealth of Love” and

that is what I like to call it. When

we pray for the coming of God’s commonwealth, what sort of picture do we have

in mind? “Thy kingdom come on

earth”...? It may be a bit overwhelming

to think of the total picture, so let us think of one aspect at a time. Think of one thing that would be a

characteristic of the gospel commonwealth if God’s reign were here with

us: Someone might suggest that in God’s

commonwealth we would be able to trust people.

There would be no worries about kidnappers, thieves, swindlers or

cheating spouses. There would be no

poison in the products we buy and no razor blades in the Halloween treats. We would be able to go out in the street at

night without worrying about muggers or rapists. We could leave our doors unlocked. There would be no bombs, no arson, no

violence. We would be able to trust

people. Someone else may be thinking

that in the gospel commonwealth we would be able to live without pain. If God’s will were really fulfilled here on

earth, would not everyone be healthy and whole?

There would be no headaches, stomachaches and toothaches, no aching

muscles and joints, no infections, no diseases.

We would live without pain.

Another person may be thinking that in a commonwealth of love we would

live without loneliness. We would know

that there are others who care about us and understand us. Someone would be there to share in our times

of anxiety and if we felt forsaken and desperate there would be someone who

would listen and still respect us. In

fact everyone would be respected and counted as an important human being. There

would be no loneliness. Yet another

person may be thinking that in God’s commonwealth things would go right more

often. Murphy’s law would be struck from

the books. No freak accidents would

spoil our plans or ruin our lives. No

foul moods would spoil our special occasions.

No spilled soup would spoil the dinner.

No nasty tempers would spoil the family atmosphere. No bad nerves would spoil the ceremony. Finally, for once everything would go just

right.

No

doubt we have larger, world-wide expectations as well. In a commonwealth of love there would be

peace on earth. There would be no guns

and missiles, no slaughter of young soldiers or innocent civilians; no threats

of terrorism or nuclear holocaust hanging over us. In God’s commonwealth there is no hunger;

everyone will have plenty to eat. Wealth

and power will be shared equitably and used responsibly. There will be no discrimination but instead

fair opportunity for everyone no matter what their race or nationality. We could think of many more details about the

commonwealth of God. If only some of

those details could be made real in our world, how much better things would

be. The bible, of course, also gives us

visions of the reign of God in human community.

Our reading from the prophet Micah describes a picture where nations

will never again go to war or prepare for battle. They hammer their swords into plows and each

person lives in peace, without fear.

There are plenty of such passages in the bible.

The

vision for a commonwealth of God has been with us for thousands of years. It has been with us for a long time. Too long, perhaps: a lot of people have given

up on it. Most people in today’s world

hardly think about it. If you were to

mention your longing for the reign of God to a friend or neighbour you will

likely draw a blank look. And if we were

to muster up enough courage to tell our children about our hope for a

commonwealth of God they might laugh at us.

“Get real,” they would say, “look at the world around us. Just look at the mess it is in. We hardly have much chance of living out our

lives in this god-forsaken world. What

chance do we have in the face of disease and pollution, climate change,

terrorists wreaking havoc all over the place and the threat of nuclear

annihilation? You can keep your hopes

and dreams and stuff them. We’ll just

try to make what we can out of what’s left to enjoy while we still have the

chance.” Secretly, we ourselves may also

be starting to think that way and our dreams for God’s reign are deteriorating

into a fading hope for a bit of relief in the heavenly here-after. Yet we pray, every day, “Thy kingdom come,

thy will be done on earth as it is in heaven.” I

would not stop praying this prayer if I were you. As long as we still have some vision of what

a commonwealth of God might be like; as long as we still believe in goodness

and love, wholeness and truth, we should keep on praying that prayer. When we pray, we are trying to get in touch

with God, we are trying to get on God’s wavelength. When we pray we are joining ourselves to

God’s purposes; we are making ourselves at one with God’s will, at one with

what is best for God’s world and God’s creatures. When we pray with all our hearts and minds

and strength, we may just concentrate hard enough and apply ourselves

thoroughly enough to become one with God’s will. And when that happens we will understand the

secret of God’s kingdom; which is that the Reign of God is within us. The gospel of Luke sums up the teaching about

the commonwealth of God in chapter 17 verse 20 where someone asks Jesus when

the reign of God would come. Jesus

answers: “The reign of God does not come in such a way as to be seen. No one will say ‘Look, here it is’ or ‘there

it is!’ because the reign of God is within you.”

So it

may be that in spite of all our longing for God’s commonwealth to come and make

things better for us, that actually, it is already here! It has already come in such a way as cannot

be seen. Jesus teaches this in many

parables, such as the one we read in Luke 14:15-24. One day while Jesus was talking about the

reign of God someone said, “How happy are those who will sit down at the great

feast in God’s commonwealth.” That

person was thinking that it sure would be nice when God’s reign finally arrived. It would be like a long awaited party where

you would finally sit down to enjoy yourself, relieved of all your worries,

ready to bite into the ultimate of pleasures, the highly touted pie in the sky. But Jesus said, “Let me tell you a story

about someone who gave a party and invited a lot of people. When the feast was ready no one showed

up. They were all too busy with their

own affairs. As far as they were

concerned there was no feast worth going to.

That’s what the reign of God is like, it is being held right now and you

don’t recognize it, here among you. It

is here, but you don’t seem to see it.”

Why

are we so seeing impaired? Why don’t we

have eyes to see the reign of God? We

have that commonwealth right here in the midst of us and yet we don’t see it. Our eyes and our thoughts are elsewhere, our

vision is on other things. Those other things are what we see on the

surface. We look at our church and we

see first of all the externals: the

building, the work of committees, the order of service in worship. Too much focus on these structures of the

church can make us insensitive to God’s purposes. The structures themselves can lead us astray:

our sanctuary, our liturgy, our hymns can become objects of idolatry rather

than vehicles for our connection with God.

Are these structures, then, the focus of our attention? Are we so busy

dealing with such external concerns that we miss God’s invitation to the

feast? The feast has begun, the

commonwealth is here. “Open your eyes,”

says Jesus, “open your minds, open your hearts, expand your vision, expand your

faith. The possibilities for God’s reign

are enormous, the opportunities of the

commonwealth are countless.” Sure, we

can still bemoan the fact that our world is full of problems. We can’t trust people. There is so much pain and loneliness. Things are always going wrong. There is little peace on earth. There is hunger and disease, oppression and

injustice. Even the church is going down

the tubes. The list seems endless and

the problems are overwhelming. And yet,

over against this list of troubles and woes we have before us an

invitation. It is an invitation to a

feast, to a commonwealth of love, to a community which can turn the tide of

despair.

I

don’t know what the ultimate heavenly feast in eternity will be like, but I am

convinced that it will be celebrated by persons who have found the joy of God’s

commonwealth in this world. They are the

people who know the joy of building relationships of trust in a world where

there is much dishonesty. They know the

joy of sharing burdens of pain often almost unbearable. They know the joy of learning to understand

and care for each other, breaking down walls of despair and loneliness. They know the joy of finding forgiveness and

healing after things have gone wrong once again. They know the joy of making peace after a

conflict and finding reconciliation after bitterness and hatred. They know the joy of the struggle against

hunger and injustice here at home and around the world. All of these joys can be found right here and

right now in our own lives, in our own church family, in our own gospel

community. And the only thing we need to

enter these joys is a prayer in our heart: “Thy kingdom come, thy will be done

on earth as it is in heaven.” When

will that commonwealth be here? The

reign of God does not come in such a way as to be seen. No one will say, “Look here it is,” or “there

it is,” for the reign of God is within us.

“Our Daily Bread” Scriptures: Genesis 4:1-16, Matthew 25:31-40

This part of the prayer of Jesus probably doesn’t

immediately resonate with us. “Give us this day our daily bread,” That prayer may not mean very much to the

average Canadian in the 21st century. I

don’t think we feel very dependent on God for our daily food. We look after ourselves in that

department. We have jobs so that we can

earn money to go to the grocery store.

We generally manage to find enough money to get our groceries and if for

some unfortunate reason we lose our source of income we can turn to the

government for social assistance. We

don’t go to our God in heaven. So we may not really know what it is like to

pray for our daily bread and perhaps that also means that we don’t really know

what it is like to pray for anything else.

Praying for daily bread is symbolic of praying for all sorts of

things. Theologically speaking, all of

our needs are supplied by God; not by our own “bread-winning” skills or by the

government. But we have lost sight of

the wonder of God’s providence. We have

lost sight of our dependence on the Creator.

We are losing our compulsion to pray for most anything and perhaps we

don’t really want to pray anymore. We

have become independent and self-sufficient.

It is very nice for people like ourselves, in affluent countries, to be

so independent but for a substantial segment of our world’s population, things

are very different. There are plenty of

people on our planet who can do nothing other than to pray for a bit of daily

bread. I don’t intend to harass you

today with a lecture about starving people in poverty stricken countries. However, I do have stories to tell you from

my own experience living in rural Africa and my involvement in global ministries

like the Canadian Foodgrains Bank and Oikocredit. I am

struck with the fact that our prayer says, “Give us this day our daily

bread.” I have to see that “us” not

just as my own family, or any one church congregation, or Christian people in

Canada, but that “us” has to be all of the children of our God in heaven. “Give us this day our daily bread.” It would also seem that some of “us” don’t

get enough food to eat because others of us prevent the bounties of God’s

providence from reaching all of those who need their daily bread. So we’re in this together; all of us in the

global community.

“Give

us this day our daily bread.” What is it

really like to pray that prayer? I

believe that I can tell you a bit of what it is like. Again, there will be no lecture, just a

story; a story that comes from my own experience of working in African famine

relief. This story goes back a number of

years, of course, to the early days of the Canadian Foodgrains Bank. In those days we actually shipped food from

Canada to places of hunger around the world.

During the time of the so-called “Ethiopian Famine” I spent three months

on an assignment with the Canadian Foodgrains Bank to monitor a food shipment

of corn and beans from south western Ontario into a drought stricken area of

East Africa.

Because

of my immersion in biblical studies, my own experience often seems to merge

with the stories of the bible. So when I

tell the story of hunger in Africa it is for me intimately related to the story

of Cain and Abel in the fourth chapter of Genesis. This story of Cain and Abel begins with a

human being who feels dissatisfied. Cain

feels that there is something incomplete about himself and his daily life. Something is missing. He wants more than what he has. He senses the problem deep within his

spirit. The fruits of his labour are

inadequate. Even his offering to God,

the token fruit of his work and of his very being, is not acceptable. The scripture tells us, “And God had regard

for Abel and his offering, but for Cain and his offering, God had no

regard.” We really cannot know why

Cain’s offering was unacceptable. Later

reflections in Jewish theology and also in the Christian scriptures suggest

that Abel was the more genuine, the more faithful in his religious duties and

therefore the more acceptable. But the

story itself makes no mention of the brothers’ relative faithfulness and

piety. In fact both brothers seem to

have performed their religious duties with equal responsibility as far as we

can tell. And yet, Cain felt inadequate,

something was wrong, he did not measure up.

Surely even God must find him deficient.

If we are honest with

ourselves, we can sense a link with Cain, we too know that feeling of

dissatisfaction and inadequacy. We too

have known jealousy, bitterness and hatred over against those who seem to be

better off somehow or more at peace than we are. We also know what it is like to ignore

someone else’s misfortune, especially if we have some responsibility for that

misfortune and then shrug it off like Cain who asks, “Am I my brother’s

keeper?” On the other hand of course, as

good Christians we do care about others’ misfortune. That’s what our works of charity are all

about. Isn’t that what the work of our

Canadian churches’ Foodgrains Bank is all about? Still, that sense of caring was not the

essence of my experience in Africa. Much

of the time I felt like Cain who says to his brother, “Let us go out to the

field.” Of all the words in the story,

that phrase stands out for me. I don’t

believe that Cain actually intended to kill his brother out there in the

field. He felt inadequate and inferior

as we have already observed. Perhaps he

wanted to prove himself to Abel, perhaps even help him in some way or share

something clever with him. Perhaps he

had some knowledge, some expertise, something to show Abel that he, Cain, was

not a failure after all. But he did not

mean to kill him. I don’t think we

intend to cause the deaths of our sisters and brothers. So we find ourselves out in the field with

Cain and Abel; in the fields of Africa, where the age old sibling relationship

is developing on centre stage:

“Come,

let us go out into the field,” says Cain, “and I will show you some clever new

ways to make use of the land. You can

grow cash crops; coffee and tea, cotton and hemp. Never mind that these will use up your

valuable food producing acres, I will give you money for these crops and money

can buy you anything. “Let

us go into the field and I will show you where to build runways of concrete and

tar. Just think how impressed your

neighbours will be when my silver birds touch down on your soil bringing

important visitors to your land. My

fighter jets will also come to sleep in your airfields and protect your

country. “Let

us go into the field and I will lend you money to build oil refineries where

you can produce fuel for my thirsty airplanes and for the fancy vehicles I need

to drive around your country. I will

lend you money to build tourist lodges of international five star standards

where my wealthy friends can go to relax!

You, of course, will find employment in these establishments, you will

get some salary, every month. “Let

us go into the field, and if we happen to find that there isn’t any food

anymore for you to eat; never mind, I will send you food, millions of bushels

from my own fields of plenty. I will not

let you starve because I need you as a market for my own industrial products.”

And Cain rose up against his brother Abel... and killed him.

One

day, there in Africa, I caught a glimpse of Cain. I was staying in a comfortable church guest

house run by a North American mission in Nairobi. I had a nice room. There was a full-length mirror. And staring out at me from that mirror, there

stood Cain. His face was white, in a

world where most are black. He was well

dressed, in a world where many wear rags.

He was well fed, in a world where many are hungry. And in his pocket he had an airplane ticket,

back to the land of Nod, where he was doomed to live a fugitive and a wanderer,

a prisoner of his own failures.

But

this is not the end of my story. There

was a sound in the air, there in Africa; a noise; a howling, unpleasant

noise. I came to realize what it was,

that noise. It was the voice of my

brother’s blood crying to God from the ground.

When I began to hear that noise and realize its consequences and

implications,

I joined my thoughts again with those of Cain who

exclaims, “My punishment is greater that I can bear.”

It was not only the blood of Abel that was crying from

the ground. There was more blood crying

even louder. The sound of the blood

spilled in the African holocaust merged with the sound of the blood spilled

nearly 2000 years ago in a crucifixion at Golgotha. Then when the noise and the din became truly

unbearable I heard a voice, and the voice said, “My God, forgive them for they

know not what they do.” And at that

moment my sense of identity with Cain vanished.

I became one with Abel. I felt

the presence of death, of hunger, of suffering.

I no longer cared about the injustice of it all. There was no justification for anything

anymore. I only knew that I was

hungry. We, the people of Africa were

hungry. We suffered and we waited. And we waited one hell of a long time... all

the while praying, “Give us this day our daily bread.”

Finally,

food arrived. Corn and beans from

Canada. But it was not food from

Canada. It came straight from above as

far as we were concerned. It was manna

in the desert. It did not appear as a

result of the well-meaning charitable efforts of some good Christian folks in

Canada. It was an act of God; a merciful

and miraculous response to our unceasing prayers for daily bread. We had been fed, and the food was

providentially and therefore rightfully ours.

At the same time we realized that we should never have been hungry. There had always been plenty in God’s

providence for our daily bread. Thank

God for that food from Canada, but our food did not have to come from Canada! God would provide daily bread from our own

doorsteps if we could only pray together, all of us right around the world,

“Give us this day our daily bread.” People

who understand and live this prayer will share their food with those who are

hungry; but more than simply sharing they will do all they can to prevent Abel

from being killed by starvation. No one

needs to starve in our world of plenty.

Good God in heaven, give us

this day our daily bread.

“Forgive

Us Our Trespasses” Scriptures: Deuteronomy

15:1-11, Matthew 18:21-35

The theme of forgiveness

springs from the very heart of the gospel.

Anyone who doesn’t understand forgiveness cannot understand the

gospel. Without forgiveness there can be

no reconciliation, no peace, no relationship with other people and no

relationship with God. Forgiveness is a

two-sided experience. It includes the

understanding of what it means to forgive but also what it means to be

forgiven. According to Matthew’s gospel,

the whole point of praying the prayer of Jesus boils down to living forgiveness. Immediately after teaching the prayer, Jesus

says, “For if you forgive others the wrongs they have done to you, God in

heaven will also forgive you.” (Matthew

6:14) Then, later in the gospel, Matthew

presents the parable we have heard today, a parable which draws attention to

the challenge of forgiving others.

It is difficult to

forgive. It is not something we do very

readily. It often goes against our sense

of fairness and consequently our social system plays down the importance of forgiveness. After all, fair is fair. If someone does something wrong, they have to

pay for it. We have to pay for the

consequences of our mistakes. We can’t

let people get away with murder, or with robbery and treachery. How is it possible to forgive someone who has

hurt me or betrayed me? How can things

be made right with such a person? And

surely there are some things that simply cannot be forgiven. What about the crimes of serial killers or

ruthless terrorists who torture their captives and cut off their heads?

Generally speaking, one of the reasons we

find it hard to forgive people is because we tend to identify a person with

that person’s behaviour. A psychiatrist

will tell you that it is a mistake to see a person and that person’s behaviour

as one and the same thing. A good

theologian would agree with the psychiatrist.

Such a theologian once told me that God loves and accepts me as a person

even though God does not often approve of my behaviour. I have thought a lot about that over the years

and I have continued to realize how important that statement is even as I

continue to realize how difficult it is to apply it to others. When a child behaves badly, I say to myself

and unfortunately sometimes to the child, “you rotten kid.” I neglect to differentiate between the person

and the behaviour. When I see the bad

behaviour, I tend to write off the person; the person is then no good. It works the other way around too. When somebody disapproves of something I have

done, I figure they think I am no good, that I as a person am a nobody.

This tendency to write off

persons as nobodies stands at the root of our inability to forgive. When someone is a nobody in our eyes, we have

no respect for that person and we cannot readily forgive someone for whom we

have no respect. Therefore the first

step in forgiveness is to acknowledge the other person as a genuinely

respectable human being in spite of their behaviour or even their crime. We brand criminals according to their

crimes. We call them murderers and

thieves and liars instead of persons who have committed murder and theft and

treachery. This doesn’t make the crimes

any less serious, but it makes all the difference in how we can begin to relate

to those persons. They are persons, just

like ourselves. Actually there is

nothing intrinsically better about me as a person than there is about that

other one who has committed a crime; even though I don’t have a criminal record;

even though I am a God-fearing Christian; even though I am an ordained

minister.

I have used murder and

robbery as criminal examples of personal behaviour but we don’t have to go as

far as that. In fact we find it hard to

accept anyone who exhibits behaviour of which we do not approve. When we see strange behaviour we think to

ourselves, “there must be something wrong with that person.” Sometimes behaviour is wrong and needs to be

corrected but at other times there is nothing wrong with a behaviour that we

consider to be strange. Sometimes, it is

merely a matter of the appearance of a person, let alone their behaviour. Although piercings and tattoos are more

acceptable today than they were a generation ago, we are still a bit suspicious

of people with lots of tattoos. And all

those foreigners from Africa and Asia with their strange features and weird

customs, surely they have missed the mark somewhere along the way; maybe they

were left behind a bit in the evolutionary process! So we tend to judge a person on appearances

and what we can see of their behaviour.

Every culture creates standards of beauty and ugliness and then the

beautiful people are seen to be good and the ugly people are bad. We try to meet the ideal standards as best we

can. If we look beautiful and act

properly we think we are good people.

Then, if the overall impression is favourable, we can forgive one or two

flaws. Such forgiveness is a process of

weighing the “pros” and “cons,” the good points and the flaws. If the overall impression is above average

then I pass inspection. If I drop a few

percentage points, I look for a way to make it up to you. I bring you some flowers or a box of

chocolates. Then all is forgiven.

But nothing is forgiven if I am merely

catering to some standard of what is considered to be favourable appearance or

behaviour. It is the person behind the

behaviour that needs to be accepted and loved.

In the prayer of Jesus we

ask God to forgive us as we forgive others.

We pray to be immersed in God’s grace, immersed in the realization that

God accepts us and respects us as the genuine persons we are in spite of our

trespasses; in spite of those things that are offensive to the divine being who

represents all that is good. But to

apprehend such acceptance from God is at the same time to embrace the ability

to accept and respect others as the persons they are in spite of things about

them that seem offensive to us. Whether

those things in others are really offensive or not is almost beside the

point. Whether it was actual criminal

behaviour or just a perceived flaw, in a sense it is all the same. To forgive is to set our perceptions aside

and to see the other person with genuine understanding; or as the bible would say with genuine love. When we reach the point where we truly accept

another person in spite of their behaviour and appearances then we understand

God’s forgiveness because we will then have some idea what it is like to love a

person who doesn’t quite measure up to our own standards. Deep down, we know that we ourselves also

fail to be true to our own standards. One way to cope with that knowledge is to

push those standards onto ourselves and others with an iron fist. That is what fascists do. The Nazis, for example, wanted to rid the

world of anyone who didn’t have fair skin and Aryan racial features. They wanted to rid the world of diseased

and disabled people. They wanted to rid the

world of homosexual and Jewish people.

“Kill them all” was their policy and they managed to kill millions. But of course, their insanity stemmed from a

severe sense of inadequacy which they disguised as their

pseudo-superiority. They could not

accept themselves “warts and all.” They

knew nothing about forgiveness. They had

no true concept of a loving parent in heaven even though many of them claimed

to be Christians. And they committed

severe atrocities; the gravest sins this world has ever seen. Their ideal society was nothing like the

commonwealth of love that the gospel proclaims.

There is a place in God’s commonwealth for me because there is room for

my sister or brother whom I have come to love and respect in spite of any

apparent flaws or offensive behaviour or even crimes committed against me. I come to understand God’s forgiveness only

when I am able to see beyond my neighbour’s offensive behaviour and accept that

person as a sibling human being. That is

how forgiveness works and that is why we pray, “Forgive us our trespasses as we

forgive those who trespass against us.”

At the same time, forgiveness is much more than just

“forgive and forget.” Forgiveness also

requires restoration. When we start to

see each other as genuine and full-fledged sibling human beings we want to see

healing and reconciliation and a setting right of the wrongs that happen among

us. Jesus talks about forgiveness from

within a very specific context. In the

bible, forgiveness is often literally a forgiveness of material debts as in the

parable we read today and even as in the prayer of Jesus. The old translation which says “forgive us

our debts as we forgive our debtors” is a very accurate translation. In our reading from Deuteronomy we are

reminded of an ancient custom in Israel which called for the erasing of debts

every seven years. If you owed me some

money, I would have to cancel the debt in the sabbatical year. If you had become my slave, I would have to

set you free. The concept in these regulations was to restore balance in

society and to restore each person’s dignity as a full-fledged child of God in

the community. When we forgive each

other, we should also strive to restore the balance that has been destroyed by

our debts or trespasses. There should be a balance of dignity as well as a

balance of material wealth in the gospel community. In working at forgiveness, I can’t just say

“I forgive you” unless I am willing to work with you to restore your dignity in

my eyes and you are willing to work with me to restore my dignity in your

eyes. It is important to reach the point

where we both realize that something was wrong between us and we are now

willing to work hard to make it right.

Notice that this is not simply a matter of a “bad guy” paying for a

crime, but rather both parties working towards restoration and

reconciliation. Often it is extremely

difficult to do the work of restoration that forgiveness requires.

There is not much evidence that sabbatical

regulations were actually put into practice in ancient Israel and it is hard to

imagine how the balance of and dignity can ever be restored between a

perpetrator of rape and the victim let alone one who murders and the one who

has been killed. So sometimes, in this

world, forgiveness cannot be accomplished. Sometimes, the work of forgiveness and

restoration is virtually impossible. And

yet forgiveness is the only cure for broken relationships and broken

community. We need forgiveness as a

constant resource as we learn to live with each other in gospel community. Our relationships are fragile, we often step

on each other’s toes, we are quick to take offense, and at times we cause each

other harm. Then we are called to pray,

“Forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us.” Ideally, we learn to forgive others as we

acknowledge our own flaws and offenses over against God who challenges us with

a presence that is absolute goodness itself.

In Jesus, God’s absolute

goodness reached out to people as Jesus made friends with all sorts of folk,

even with criminals - that is with persons who had committed a crime. In the gospel community God’s goodness is affirmed

as we maintain healthy friendships with each other and extend our desire for

reconciliation into the world around us. So we experience God’s forgiveness as

we forgive each other. We grow in

communion with the One who is love and goodness as we grow in healthy

friendships with one another in the gospel community.

“Lead Us Not Into

Temptation”

Scriptures: Genesis 3:1-8, Matthew 4:1-11

“Lead

us not into temptation but deliver us from evil.” The parallelism of the poetry in this line of

the prayer of Jesus gives us two sides of the same thought. Avoiding temptation entails deliverance from

evil and vice versa. Much of what we

find in the bible on this theme places the focus on temptation and so it is

this aspect of the phrase that we will focus on as well. Our scripture readings today also help us to

gather our thoughts in particular ways.

The reading from Genesis helps us raise questions about the nature of

temptation and the reading from Matthew helps us define some categories of

temptation. Let us begin with some

thoughts about the Genesis passage.

The

story of the eating of the forbidden fruit introduces one of the common themes

of the bible, that life in this world can be a testing experience. We humans are faced with all kinds of

challenges and testing, presumably so that we might discover what is good for

us. Through trial and error we discover

God’s purposes; we come to know wholeness and salvation. Ironically, part of the testing process seems

to be that we are continually faced with tempting alternatives to real

salvation. We discover genuine human

wholeness by testing and rejecting the phony alternatives, no matter how

tempting they seem to be. Life then is

an experience that contains a lot of testing.

The bible doesn’t tell us exactly why life is like that. It simply presents us with this reality: “Life is like that and it has been so from

the start.” When Adam and Eve, the

prototypical humans, arrive on the scene in the bible they are presented to us

as living in a condition of wholeness and happiness. Life couldn’t be any better than it is for

them. But then they are tempted with the

idea that something else could be even better.

This temptation is symbolized by the presence of a forbidden fruit in

their lovely little world. They start to

think that a taste of the forbidden fruit might make their lives even better

and that they could be more than what they were created to be. They would become super-human. They would be like God. Of course they ate the fruit only to discover

that their happiness did not lie in becoming something other than what they

were. The pursuit of that deceptive

dream resulted in misery and they found themselves worse off than they were

before. It was as if God had said to

them, “Get a life folks. Find your

happiness in the life that you have been given, you won’t find it in a phony

dream that has nothing to do with reality.”

The

story of Adam and Eve who eat the forbidden fruit is the story of us all. We are constantly challenged to test the

limits in our quest to discover who we are.

Often that testing is the hard testing of what the bible calls

temptation. We are faced with this

testing in big ways and little ways in every aspect of our lives. In order to be healthy and happy and whole we

need to know our limitations. But these

limitations are learned by trial and error, often by breaking limits in the

pursuit of some temptation. We all

know that we would be most healthy and therefore ultimately most happy, if we

limit ourselves to a certain intake of calories each day. But where does the limit lie? And what of all those goodies that tempt us

to exceed the limit? Temptation is our

constant companion. When we see a

delicious piece of cake within easy reach, it seems that we would be so much

happier if that piece of cake were melting in our mouth, even if it is coming

to be the third helping. When we smell

the aroma of freshly brewed coffee it seems that we would be wonderfully

satisfied if another cup could be placed to our lips, even if we have already

had several that morning. Then we end up

with a stomach-ache and bad nerves and a miserable disposition. We want to overstep our limits not just in

eating but also in the speed we travel on the highways, in our accumulation of

wealth, in our power over other people.

But when we do overstep our limits we put ourselves and others in

danger; we throw away our health, our happiness and sometimes our very

lives. There are countless people in our

world suffering and dying because they went beyond the limits. Some folk are too fast or reckless on the

highway and end up in accidents. Some

consume too much alcohol resulting in a ruined life. Some have indiscriminate sex with multiple

partners resulting in diseased bodies and broken personalities. There are countless little things that you

and I are doing to ourselves to bring destruction into our lives. There are so

many temptations that we cannot ignore, temptations that can lead to

destruction but are at the same time necessary to help us learn the limits and

find our happiness within those limits.

The

collective wisdom of human experience warns of destruction on the other side of

temptation and the collective wisdom of Christian experience tells us to be

pro-active in dealing with evil. So

Jesus teaches us to pray: “Lead us not into temptation but deliver us from

evil. According to Jesus, staying in

touch with the Spirit of God will make the testing easier, or at least less

dangerous. When we are in touch with

God’s presence and purposes, we will have a better handle on the hollow

promises of every-day temptation.

Staying connected with the will of God has the effect of leading us away

from temptation rather than into it.

Being in touch with God is easier said than done, of course. However, as followers of Jesus we have some

further guidance on the subject of temptation.

A first step for a Christian is to see how Jesus resists evil by overcoming

temptation. So we turn to the story of

the temptation of Jesus in the wilderness.

In his wilderness experience, Jesus faced temptations that are much like

the hard testing we face in our daily lives.

These temptations held hollow promises filled with alternatives that

looked good on the surface but would wreak havoc in the end:

“If

you are God’s son, order these stones to turn to bread.” Here we have the hollow promise of a

quick-fix solution which ignores deeper needs as well as the consequences of

its own magic “fix.” Give a hungry

person a fish instead of sharing the secrets of fishing; give an unhappy person

a bottle of bubbly, or a face-lift; win the lottery, find yourself a playmate

on the internet. But turning those

stones into bread is not going to solve anything in the end. Learning abundant life, learning wholeness,

learning salvation is more than trying to land yourself a free lunch.

“If

you are God's son, throw yourself down from the highest point of the

temple.” Here we have the hollow promise

of a phony image. “Make yourself larger

than life. Bolster yourself up with a

fine suit of clothes, plenty of make-up and jewelry, a special title in front

of your name, an appearance on television; perform some magic for the crowd;

they will love it and they will like you.

You will have them eating out of your hand and doing whatever you want

them to do.” But we see that Jesus stays

away from fancy clothes and special titles and magic tricks. When the disciples start to think that Jesus

might be the Messiah, Jesus says, “Don’t tell anyone.” When someone is healed in the presence of

Jesus they are told, “keep this quiet.”

Jesus makes no pretentious claims.

Jesus does not give the impression of being larger than life. Jesus does not “put God to the test” as the

story says. (Notice the interesting

irony in the concept of “putting God to the test” as we fall into temptation. It is, of course, the image of God within us

with which we are messing around.)

Then

the tempter took Jesus to a very high mountain and showed him all the kingdoms

of the world in all their greatness.

“All this I will give you,” the

tempter said, “if you kneel down and worship me.” Here we have the hollow

promise of a shortcut to success; the easy path to power; “how to win friends

and influence people.” There are lots of

quick ways to the top in this world, but always at the expense of others. I can bully my way into being kingpin in my

family or in my church or in my place of employment by manipulating the others

around me. If I do that I have opted for

the way of the devil. Jesus could have “had it all” so to speak. He had the smarts and the personal resources

to make it to the top. Yet he chose the

way of love and justice in egalitarian community. In that choice, Jesus overcame temptation,

resisted evil and ultimately at great personal cost brought upon humanity a

renewed experience of salvation. Jesus

gives us a renewed sense of what it means to be whole as human beings and what

it is to make real the image of God within us.

Ironically,

whenever we begin to sense the image of God within us it seems that the spirit

casts us into a desert of temptation.

Evidently it has to be that way.

There is no faith without doubt and no security without the challenge of

temptation. To find real peace, real

security, real wholeness, I first need to face and resist the temptation of

looking for fulfillment and security in the quick satisfaction of my whims and

urges, in relying on a phony image of myself and in accumulating power over

other people. Unless I deal with these

temptations and reject them I will never find real peace, real security, real

happiness.

The

salvation that we seek in deliverance from evil is an elusive commodity and we

have good reason to fear the temptations that stand in the way. We confess that fear when we pray, “Lead us

not into temptation.” We need to confess

that fear daily for then we remember that temptation is with us all the

time. Yet we know that in solidarity

with Jesus we can face the temptation without falling into it and thereby

resist the forces of evil as Jesus did. Jesus

overcame temptation by accepting an essential human self and rejecting a phony

self-image built on false self-satisfaction and the abuse of others. A genuine human self was enough for Jesus

because that self entails the image of God within, which Jesus embraced and

lived out in all its fullness. Hence we acknowledge Jesus as both human and

divine. We want to walk in the footsteps

of Jesus. We will not manage as well as

Jesus did. We are not God incarnate as

Jesus was. And yet we too carry the image

of God within us and the fact that Jesus lived a perfect life by deliberately

staying within the limitations of being human - that fact gives immense hope to

us. Living into this hope means

salvation for us, it means deliverance from evil, which is our fervent

prayer. Good

God, lead us not into temptation but deliver us from evil.

“The

Power and the Glory”

Scriptures: Isaiah 60:19-22, Acts 12:20-23

At the

end of the prayer of Jesus we say, “For thine is the kingdom, the power and the

glory for ever and ever.” There is some doubt about whether

this phrase belongs with the prayer.

Many bibles don’t include it although a footnote often explains that

words to this effect can be found in some ancient texts which are deemed to be

relatively unreliable. Apart from the

fact that these words are in doubt from a textual point of view, they might

also seem uncharacteristic on the lips of Jesus. Jesus speaks of simple things like seeds and

sowers and daily bread; of sheep and coins and people in debt. It is unlikely that Jesus was much of a fan

of power and glory.

Power

and glory are dangerous commodities to be handled with great care in the gospel

community. Jesus often directed

attention away from the quest for power and the desire for glory. When James and John fantasize about holding

prestigious positions in the realm where Jesus reigns, Jesus warns them that

“you do not know what you are asking.” (Matt 20:22) In the gospel community, greatness comes

through serving others not through “lording it over them” in positions of

power. (cf Matt 20:25ff) The New Testament as a whole condemns those

folk who claim power and glory for themselves.

King Herod is described as such a person and as we read in Acts 12, his

death is attributed to his self- glorification.

Herod took the glory for himself, he did not give the glory to God. (Acts 12:23)

Of course the point of the last phrase of the prayer of Jesus is to do

exactly what King Herod failed to do, that is to give the glory to God. “For thine (God) is the power and the glory

for ever.”

“For

thine is the power and the glory.” The

early gospel community soon realized that this has to be a constant theme in

the life of its members lest they fall into the idolatry of glorifying their

institutions or certain individuals in the community. Our tendency to glorify our institutions or

important people is very strong. The

persons and institutions of royalty have been given power and glory throughout

the ages. Along with King Herod, we can

find all sorts of figures in the bible that lay claim to power and glory. They are even glorified with phrases much

like the one we are reflecting on here.

In the book of Daniel, King Nebuchadnezzar is described as the one who

has the kingdom, the power and the glory. (Daniel 2:37) And although Nebuchadnezzar is hard to

identify as an actual figure from history, the kings of Babylon were indeed

persons with awesome power and glory.

Even in the church after the time of Jesus, the power and the glory of

the clergy increased with a vengeance.

In the medieval church the clergy at the top held tremendous power and

lived in opulent glory. (And don’t think

that the people did not admire them!)

The church as an institution has often become the object of

glorification as well. Some of the most

glorious real estate in the world is owned by the church. Powerful customs and church laws have had

immense influence and control over the lives of countless human beings.

At

times, the church has misused its power.

People have suffered at the hands of the church. Human beings have been abused and even

murdered, God’s children have been oppressed and enslaved by the church. That’s what happens when the church as an

institution gets the dominion and the power and the glory. Jesus spoke about this, in one of the core

sayings of the gospel: “Human beings were not made for the Sabbath” Jesus said,

“but the Sabbath for human beings.”

(Mark 2:27) The Sabbath as a

glorified institution could have oppressive power over people and the same has

often been true for the church. Jesus

had a profound understanding of the dangerous consequences of glorifying

persons and institutions. That’s why

Jesus refused to bear the title “Messiah.”

When Peter named Jesus with that title, Peter was told “Get behind me

Satan!” (Mark 8:33) Jesus did not want

power and glory and surely Jesus did not want the gospel community to be a

church of power and glory!

So,

what did Jesus want? As far as I can

tell, Jesus wanted to call a community into being which would fulfill God’s

purposes for God’s people. This gospel

community was not meant to be Christian or Jewish or any other particular

religious culture. It was simply meant

to be a community of human beings that honoured the essence of the vision of

Shalom spelled out by the prophets of Israel.

As we have seen in our analysis of the prayer of Jesus, the gospel

community is to be a commonwealth as much as a kingdom where everyone has their

fair share of the community’s resources be they spiritual, material, or

political.

The

prophets of Israel did not categorize the resources of the community into

separate categories. The fair

distribution of material resources went hand in hand with spirituality and

politics. In Isaiah 60:19-22, the

peoples’ righteousness is equated with a fair possession of the land and within

such Shalom, God is glorified. According

to the gospel, God is glorified when things are right in the community. God is glorified when debts are

forgiven. God is glorified when people

get their daily bread,. God is glorified

when evil is resisted. God is glorified

when the reign of God is claimed and put into practice in the gospel

community. God is glorified when

reconciliation takes place. According

to the New Testament, particularly in John’s gospel, the greatest glorification

of God happened in the crucifixion of Jesus.

Not in the resurrection, not in the ascension, not in the birth of the

church, but in the crucifixion, in the bleakest moment of the entire gospel

story. This is so because only the crucifixion

can shock us into a genuine awareness of the utter evil and ultimate impotence

of abusive power and false glory. When

we claim Christ and Christ crucified, as the apostle Paul would say, we

acknowledge the ultimate abuse of power in the killing of Jesus and we sense

very quickly and clearly that our own abuse of power in various ways, big and

small, undermines the glory of God as well.

In that realization (when we claim Christ crucified) there comes a deep

yearning for making things right, a compulsive drive for reconciliation with

those whom we have wronged and therefore also with God. The crucifixion of Jesus has this effect on

us and as such it brings about the glorification of God, along with a subsequent

understanding and celebration of resurrection.

Then, in the words of the New Creed, “We proclaim Jesus, crucified and

risen.”

Power

and glory are given to God when they are distributed fairly in the gospel

community and in all creation. Wherever

power is abused and glory corralled by an elite, there is no reign of God. Hierarchy and patriarchy have been hallmarks

of the church but they are not gospel structures; they undermine the reign of

God and steal God’s power and glory. It

is no accident that children were abused in residential schools run by the

church. It is no accident that women

have been ignored and exploited and sometimes destroyed by the church. It is no accident that people come in to

the doors of our churches and after a taste of hard-line religion - never come

back. We say, often enough in our

prayers, “Yours, O God, is dominion and power and glory,” and then without

thinking, give the power and the glory to the clergy and the church; to the

organ and the stained glass windows.

Somehow we equate these things with God.

After all, heaven is full of stained glass and organ pipes is it

not? And it is kind of nice to see the

minister wearing a beard and a long robe; that’s what Jesus wore, right? Then when the time comes to sell our church

buildings and amalgamate our congregations into one gospel community - we can’t

do it. Our beloved institutions and